Author Meg Eden talks about Neurodiverence and YA Horror with ‘The Girl in the Walls’

A unique book courtesy of Scholastic Press.

About five years back, I was running an entertainment review website called The Workprint, where I crossed paths with YA novelist, poet, and prose teacher Meg Eden. She and my friend Mary Fan were rallying YA writers for something called the Nerd Girls Book Blog Tour, to highlight a few budding novelists and authors of a few writer publications at the time.

I was asked to review Meg’s debut poetry collection, Drowning in the Floating World, about the 2011 earthquake, tsunami, and Fukushima disaster in Japan. As it reads, the poetry was equal parts lyrical as it was unsettling, worthy of a pick-up.

But here’s the kicker: one month later, COVID-19 crashed into our lives, disrupting all of our lives as we know them. And suddenly, Meg’s disaster poetry felt less like art and more like a preview of our world to come.

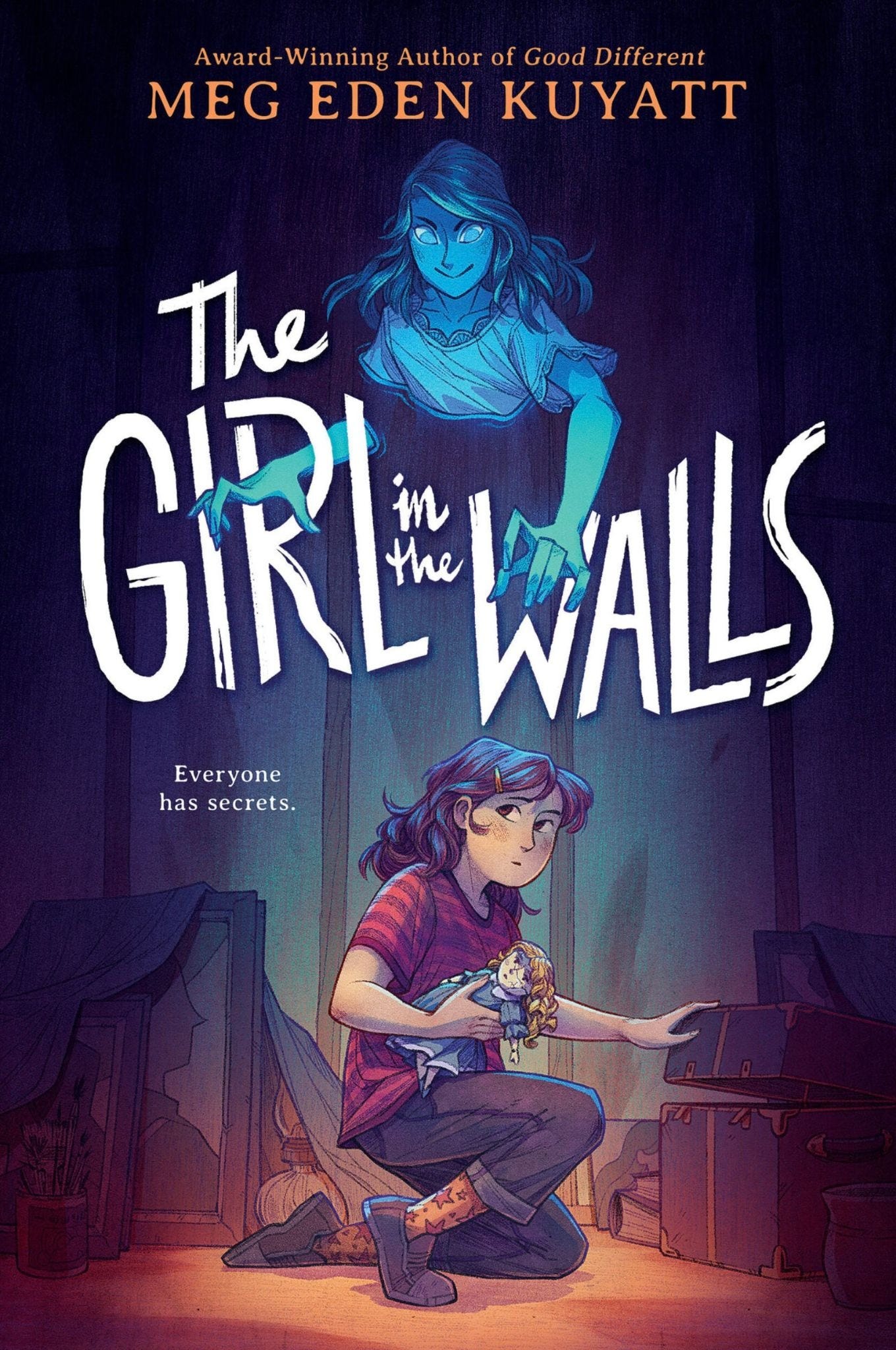

Disaster. Fallout. Isolation. Eden’s work as an author has never felt more relevant. Which brings me to her recent book of work: The Girl in the Walls. On paper, a YA ghost story about a neurodivergent teen who hears voices coming from inside her house. In practice, it’s a psychological pressure cooker about hidden rooms, hidden minds, and what happens when society decides certain people are better off out of sight. A unique book worthy of checking out.

I sat down with Meg to talk about books about hidden spaces, haunted people, and why the scariest monsters are the ones we build ourselves. Here’s our conversation.

Edited for clarity.

In college, I loved reading The Yellow Wallpaper, a feminist horror story by author Charlotte Perkins Gilman that was about hearing voices in the wall. Did that story inspire this? What possessed you to write Girl in the Walls?

MEG EDEN: That’s so funny you mention it—I hadn’t read “The Yellow Wallpaper” until after I wrote this book, but there are definitely some similarities!

I had a very upsetting experience where I saw someone I care very much about being treated unfairly. The whole experience made me think about how neurodivergent people are treated unfairly, and that if I didn’t mask as much or was less “convenient” to those around me, would I be treated differently? I tried to write directly about those feelings at first, but they were so big and awful that I was getting nowhere. So I decided to, like Emily Dickinson says, “tell it slant.” I needed something beautiful and strange to lift me out of the ugly, which is what I think is the power of speculative fiction—even horror. There’s a magic and a distance from the real-world ugly.

At first, I played with time travel, but with time, I discovered, instead, the idea of using a ghost-girl. Through the ghost, I could unload my heavy, awful feelings. I could get out, through the ugly, how powerless I can feel, but also envision possibility, joy, and healing. The fantastical gives us a little more breathing room for possibilities and hope, and making the ending we really want to see in our world.

When we first met, I reviewed a book of poetry you’d written in verse, set in Japan, about the aftermath of a large-scale disaster. Have you also written this horror book in poetic verse?

MEG EDEN: Yes. My background is in poetry, and when I have a concept that is feelings-driven, where the feelings are too big for prose, I go to verse (like with that poetry collection Drowning in the Floating World). Fortunately, my editor at Scholastic also likes my verse, so it’s a great fit!

I think for horror, it’s an interesting intersection, using verse, as it leaves room for the unsaid, for the reader to feel and imagine the horror from their own perspective. I’m honestly surprised I haven’t seen more horror in verse yet!

Tell us about your main character, V. From the description here, V is neurodivergent. Why was this essential to this story?

MEG EDEN: V starts out loving her autism—until people in her world make her feel small for it, and she begins to wonder if being different is all that great after all. I think my favorite horror, even though fantastical, has a grounding in the real world.

For this story, the real horror is ableism, the way we have and continue to treat neurodivergent people unfairly. But also, for horror, we need that rooting in fear, and I think for V that fear is that her autism, even if she loves it, alienates her from the love and acceptance of others.

I don’t think V’s wound, her fears, or really any of the horror in this story would work without her neurodivergence.

Fascinating. For sure, it’s hard to address ableism in fiction, though family can be a great way to examine it. That said, can you tell us more about V’s grandmother, Jojo?

MEG EDEN: Jojo is that difficult, hurtful person in V’s life who stifles her neurodivergent joy and is critical. I think most of us, if we’re honest, have a Jojo in our lives, someone who doesn’t seem to understand us or accept who we are. V and Jojo seem like total opposites by all appearances, but people are more complicated than we might initially think. Sometimes, people drive us up the wall because they’re similar to us in ways we don’t expect. Sometimes, because we have the same insecurities, but we don’t want to admit seeing that in ourselves. We all think we’re the hero of the story; we all act, thinking we’re doing the right thing most of the time. So while Jojo may be hurtful, I hope by the time you finish the book, you see that she is complicated and messy, like all of us.

Haunted house stories tend to lean into the ghosts of the past. The trauma about the unspoken and unsaid. Does yours? Tell us more about the setting this takes place in?

MEG EDEN: Yes, absolutely! Jojo’s house is old and is haunted both metaphorically and literally. I don’t want to spoil it, but I’ll say that haunting is related to generational trauma and neurodivergent trauma, and how if we don’t deal with deeper issues, they will continue to linger in our lives and our legacy. There are things Jojo hasn’t dealt with in her life, and this is reflected in the house’s structure: there are rooms papered over, rooms abandoned and locked away. But it’s also reflected in the horror and supernatural aspects of the story.

I think this is another reason why I loved and needed verse for this story—it has a literal, narrative layer, but also metaphoric layers on haunting, trauma, ghosts, internalized ableism and masking…and I think the poetry allows for those double layers to work together in a way that would be harder in prose.

It’s a great way of being different. How’s the reception of the book so far?

MEG EDEN: It’s hard to know for books, especially middle grade, right away, but quite good I think, with the best readers being kids! I had the opportunity to sit in at a kid’s book club at my local bookstore for the book, and the way they so deeply and passionately engaged with the text, and remembered details I wrote but had forgotten, moved me so much. I’ve found it interesting that readers either seem to really love it or don’t seem to get it. I think it’s probably a good indicator of neurodivergence—if you’re neurodivergent, you’ll probably connect with it in some way. If not, you may struggle to understand or resonate with the metaphoric levels.

Interesting. What’s the wildest reaction you think you’ve gotten from a reader?

MEG EDEN: For this book, my favorite reaction is that a kid I know drew me V’s sock collection and gave it to me—I have them hanging in my office now! Most recent reaction in general, I was tabling at a book event and found that someone had been at my table a couple hours, so immersed in reading one of my books! That felt like the best compliment I could get.

Finally, what do you hope readers to take away from The Girl in The Walls?

MEG EDEN: I hope all of us will be challenged to see each other with empathy and nuance. We often want to put people into boxes: this person’s great; this person’s horrible. But most people are too messy for a single box. We contain multitudes. I think this is hardest to remember when there’s hurt, but I think this is perhaps when it’s most important to strive to see people’s humanness.

We are in a particularly divisive time. There is so much hate and anger and assumption-making happening, and it’s scary and upsetting. We have so many ways to speak, but so often feel unheard or spoken over. I know I make so many conclusions about people who do things differently from me, and I have to proactively slow down, listen and ask questions. Sometimes I’m really surprised by what I hear! I learn, and as a result, I grow. I want to be someone with a spirit of willingness to listen and grow, and I hope to encourage my readers to seek this as well.

Also, emotions are messy, like people. Often, the rhetoric I hear about emotions are “follow your heart” but I think this is complicated. There is a value to listening to and being aware of our feelings. They can be good warning signs that something is wrong, or that we need to change something in our lives. But if we let feelings be unchecked pilots, I think that’s dangerous. I know my feelings are not reliable narrators, and do not always tell me what’s true. They also change very quickly! I wanted to talk about this messiness for kids, because I think it’s really, really important we have a healthy, balanced view of our feelings. Feelings should be validated, but also put into perspective of truth.

______

You can get a copy of THE GIRL IN THE WALLS wherever Scholastic Books are sold.

Christian Angeles is a writer and entertainment journalist with nearly a decade of experience covering comics, video games, and digital media. He was senior editor at The Beat during its Eisner Award–winning year and also served as managing editor of The Workprint. Outside of journalism, he writes comics and books.